The city that sues itself: how the Privacy Advisory Commission enables conflicts of interest

Oakland’s tangled web of citizen commissions takes authority (and accountability) out of the hands of elected officials

Oakland Report is taking a closer look at the City of Oakland’s many appointed citizen commissions, starting with those related to public safety.

The city that sues itself

Oakland’s Privacy Advisory Commission (PAC) created a surveillance technology ordinance that allows residents to sue the city for violating it. Then the commissioner who co-wrote the ordinance sued the city for violating it and won a $30,000 settlement.

Brian Hofer, who represented the City of Oakland as a citizen member of the PAC while also serving as the executive director of the nonprofit Secure Justice, had a prominent role in writing the ordinance. He then sued the city for violating the ordinance, while still sitting on the PAC. The city council agreed to a settlement to implement certain policies and paid Hofer and Secure Justice $30,000 for attorney fees and costs.1

Hofer, along with his nonprofit Secure Justice has brought similar lawsuits against other cities, including:

The Contra Costa Sheriff’s Department after Hofer was subjected to a traffic stop in 2018. Automated license plate readers had flagged as stolen the rental car he was driving. (It turned out that the car had been stolen a month earlier.) The case was settled in 2020 in Hofer’s favor for $49,500.2

The City of Berkeley on two occasions for violating its sanctuary contracting and surveillance technology ordinances, which Hofer helped to write. According to Hofer’s bio on the Secure Justice website, the city agreed in both cases to cure the violations and pay Hofer and Secure Justice’s attorney fees and court costs.3

The City and County of San Francisco for violating its facial recognition surveillance technology ordinance, which Hofer helped to write.4 (The case is still working its way through the court system.)5

Hofer’s term on the PAC expired in March 2025 after serving nine years. Oakland allows commissioners whose terms end to continue serving in “holdover” status until a replacement is appointed. Hofer continued to serve in that status until the city council replaced him on November 4 with a new commissioner.

Hofer’s example is a case study of how Oakland’s citizen-run commissions enable conflicts of interest and self-promotion to run virtually unchecked — all with the imprimatur of officially representing the city’s interests.

This article explores how the PAC arrived at this juncture and why it is emblematic of a broader problem with Oakland’s commissions, including city leaders’ failure to ensure ethical standards and accountability for the commissions’ activities.

Expanding citizen oversight and control over the use of public resources

The City of Oakland has four separate, non-elected citizen oversight commissions and bodies with authority over aspects of public safety, each with expansive and at times overlapping powers.

Some of these commissions, like the PAC, have expanded their own power through policies and ordinances they created. As a result, some commissions now hold gatekeeping and even veto authority over key municipal decisions that once were reserved for elected officials and civil service professionals.

And the commissions continue to seek ways to expand their power even more.

For example, the PAC proposed earlier this year a new cybersecurity oversight ordinance that would extend the PAC’s reach beyond surveillance technology to include essentially all data security across the city. If codified into law, the ordinance would position PAC as one of the most powerful citizen cybersecurity oversight bodies in the country, with the authority to review virtually all the city’s technology contracts, networks and breach response plans, among other sensitive information.6

See this related article:

In another example, the citizen-run Oakland Police Commission wrote a Militarized Equipment Ordinance to comply with a new state law.7 But Oakland’s ordinance went further than the law required: it gave the police commission veto power over all requests to purchase, deploy, or maintain police equipment such as armored vehicles, drones, and rifles.8

The police commission also is legally empowered to issue subpoenas and can even terminate the police chief for cause, an extraordinary power typically reserved only for mayors, city councils or city administrators.

Even further still: Oakland’s newest citizen oversight body, the Oakland Public Safety Planning and Oversight Commission (OPSPOC) now controls the allocation of $45 million annually in public safety tax revenue.9 Appropriating and authorizing expenditures of public resources is a fiduciary role typically reserved for city councils, who are accountable to state and federal laws governing municipal finance in addition to being politically accountable to voters.

Public fears of surveillance lead to expansive new citizen oversight powers

In 2013, the city moved to integrate data from license plate readers, street cameras, and facial recognition data across the city, in an expansion of its centralized surveillance hub known as the Domain Awareness Center. The move was strongly opposed by civil liberties advocates concerned that it would create a mass surveillance system that lacked privacy safeguards.10

Community advocacy organizations including Oakland Privacy11 and the aforementioned Secure Justice helped orchestrate a campaign to advocate for citizen oversight of the city’s use of surveillance technology.

Their efforts culminated in 2016 with the creation of a citizen-run Privacy Advisory Commission. The PAC was empowered to oversee all surveillance-related technology used by city departments, including proposals, procurement, policy, equipment, and applications.12

Oakland’s PAC appears to be the only citizen-run commission in the nation with such an expansive scope.13 With some limited exceptions, most other U.S. cities rely on various combinations of internal departmental reviews, executive authorizations, and legislative oversight of surveillance technology.14

Layers of approval create delays and escalate costs

Oakland’s overlapping layers of citizen-run oversight have produced a complicated system in which approvals of policies, purchases, and updates are extended up to six months and in some cases far longer.

Procurements of certain equipment that are routine in other cities can require multiple commission hearings, city council actions, and federal monitor approval — creating substantial delays and straining the city’s administrative capacity while costing thousands of dollars in labor and overtime.

For example, the PAC expanded its authority in 2018 by creating the Surveillance Technology Ordinance, requiring all city departments to obtain PAC and city council approval before acquiring or deploying surveillance equipment. (As mentioned above, it also introduced a mechanism for residents to sue the city for violating the ordinance.)15

The citizen-run police commission and OPSOC also have significant review and approval authority over policies, procurements and contracts, especially those related to public safety equipment and technology.

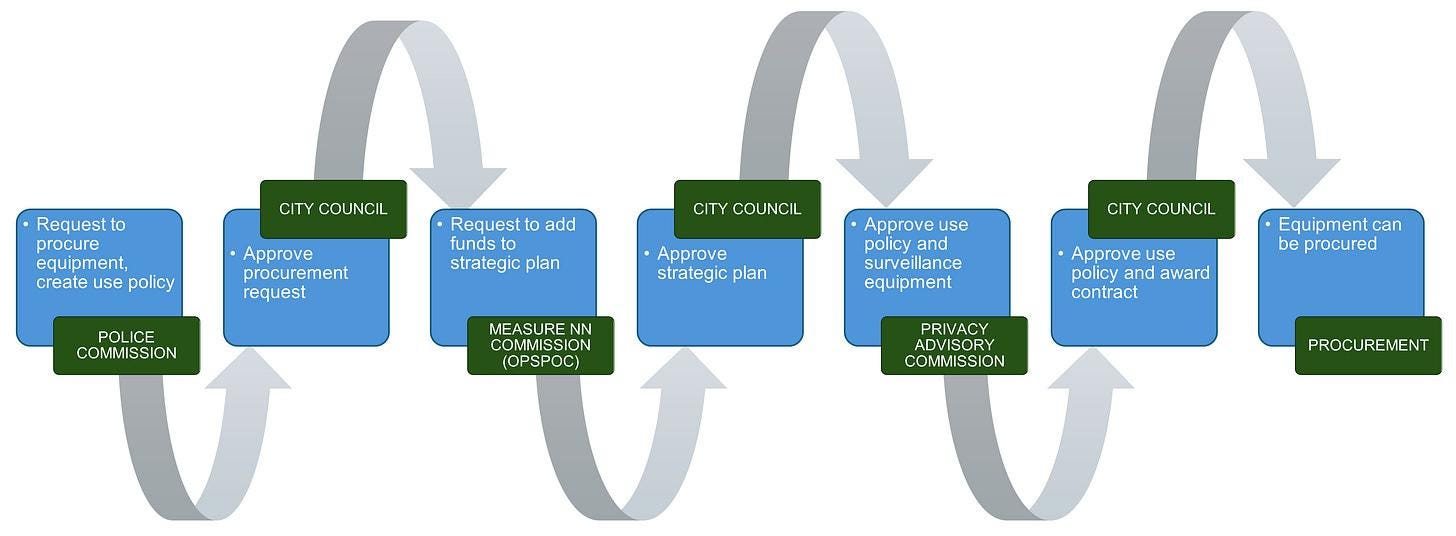

To use a hypothetical example based on a typical real-world application, up to six layers of formal review and approval would be required for the city to use Measure NN funds to purchase a drone that is categorized as militarized equipment (Figure 1, above).

Who oversees the overseers?

Public participation and influence in civic affairs are essential to good governance — as are ethics, honesty, accountability, and civic responsibility. Citizen-run commissions were created to increase public transparency and influence, but over time they have shifted decision-making authority away from Oakland’s elected leaders and into the hands of non-elected citizen appointees.

City council members are the elected governing board and fiduciary officers of the city, legally accountable to state and federal laws governing municipal finance in addition to being politically accountable to voters. Yet council members have at times found themselves unable to effectively direct certain decisions and policies concerning the use of public resources that are now fully controlled by citizen-run commissions like the PAC.

Members of citizen-run commissions are not subjected to the same levels of public scrutiny or vetting, and they operate with far fewer and weaker accountability mechanisms than elected officials. The public interest is not well served when non-elected commission appointees take the authority (and accountability) for the stewardship of public resources out of the hands of elected officials and the civil service professionals who work under those officials’ authority.

If you found this article informative, please consider donating. We are a volunteer-run, 501(c)(3) charitable nonprofit organization based in beautiful Oakland, California.

Our mission is to make truth more accessible to all Oakland residents through deep investigative reporting and evidence-based analysis of local issues.

Your donation of any amount helps us continue our work to produce articles like this one.

Thank you.

See this related article:

City of Oakland. “Concurrent Meeting of the Oakland Redevelopment Successor Agency and the City Council.” Adopt A Resolution Authorizing And Directing The City Attorney To Compromise And Settle The Case Of Secure Justice, Inc. And Brian Hofer V. City Of Oakland, Alameda County Superior Court Case No. RG21111681, City Attorney File No. X05345, For Agreement To Perform Certain Mandatory Duties And Payment Of The Sum Of Thirty Thousand Dollars And Zero Cents ($30,000.00). Agenda item #6.23, Dec. 19, 2023. https://oakland.legistar.com/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=6447311&GUID=BAFFCC7B-212B-4B0A-B844-FA9B4A5283A5

Fernandez, Lisa. “Sheriff pays East Bay privacy advocate nearly $50K in license plate reader case.” KTVU Fox 2 News, Nov. 16, 2020. https://www.ktvu.com/news/sheriff-pays-east-bay-privacy-advocate-nearly-50k-in-license-plate-reader-case

Secure Justice. Brian Hofer, Chair and Executive Director, Bio. Nov. 15, 2025. https://secure-justice.org/hofer-bio

Wadsworth, Jennifer. “SFPD skirted facial-recognition ban, lawsuit says. Hundreds of cases could be in jeopardy.” The San Francisco Standard, July 18, 2024. https://sfstandard.com/2024/07/18/san-francisco-police-facial-recognition-violations/

Secure Justice, Inc. v. City and County of San Francisco, July 16, 2024. Case No. CPF-24-518631. San Francisco Superior Court, https://webapps.sftc.org/ci/CaseInfo.dll?CaseNum=CPF24518631

City of Oakland Privacy Advisory Commission. “Meeting Agenda, June 5, 2025.” The No Stolen Data Ordinance. City of Oakland, California, p. 84, item 4.(c).1. https://www.oaklandca.gov/files/assets/city/v/1/public-meetings/privacy-advisory-commission/2025/privacy-advisory-commission-meeting-agenda-packet-for-6-5-25.pdf#page=84

California State Assembly. “AB-481.” Law enforcement and state agencies: military equipment: funding, acquisition, and use, Sept. 30, 2021. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=202120220AB481

City of Oakland. “Oakland Municipal and Planning Codes.” Regulations On City’s Acquisition And Use Of Military And Militaristic Equipment, Chapter 9.65. https://library.municode.com/ca/Oakland/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=TIT9PUPEMOWE_CH9.65REACUSMIMIEQ

Mandal, Rajni. “Measure NN’s oversight commission wields unprecedented citywide power.” Oakland Report, Oct. 7, 2025. https://www.oaklandreport.org/p/measure-nns-oversight-commission

BondGraham, Darwin and Ali Winston. “The Real Purpose of Oakland’s Surveillance Center.” East Bay Express, Dec. 18, 2013. https://eastbayexpress.com/the-real-purpose-of-oaklands-surveillance-center-1/

Oakland Privacy. Nov. 15, 2025. https://oaklandprivacy.org/

City of Oakland. “Ordinance No. 13349.” Establishing The Privacy Advisory Commission, Providing For The Appointment Of Members Thereof, And Defining The Duties And Functions Of Said Commission, Jan. 19, 2016. https://www.oaklandca.gov/files/assets/city/v/1/boards-amp-commissions/documents/pac/privacy-advisory-commission-final-ordinance-13349-cms.pdf

Alan Greenblatt. “What Cities Can Learn from the Nation’s Only Privacy Commission.” Governing, Feb. 21, 2020. https://www.governing.com/next/what-cities-can-learn-from-the-nations-only-privacy-commission.html

Chivukula, Ari and Tyler Takemoto. “Local Surveillance Oversight Ordinances.” University of California, Berkeley, School of Law, February 2021. https://www.law.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Local-Surveillance-Ordinances-White-Paper.pdf

City of Oakland. “Oakland Municipal and Planning Codes.” Regulations On City’s Acquisition And Use Of Surveillance Technology, Chapter 9.64. https://library.municode.com/ca/oakland/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=TIT9PUPEMOWE_CH9.64REACUSSUTE

Thank you for shining a light on this! I recall seeing the police chief complain of the difficulty in procuring necessary equipment. These Jacobin commissions are, at best, suffocating good governance. They also seem like fertile ground for corruption.

Another important story based on verifiable facts - not ideological (left or right) assertions.