Measure NN’s oversight commission wields unprecedented citywide power

Oakland’s newest citizen commission now controls $45 million a year and the city’s overall public safety strategy.

When Oakland voters approved Measure NN in November 2024, many thought they were simply renewing a familiar public safety tax to provide supplemental funding to police, fire and violence prevention. Instead, they set in motion one of the biggest shifts in power Oakland has seen in years. The measure didn’t just raise $45 million annually, it created a new unelected and unaccountable civilian body with sweeping authority over how those funds are spent and how the city defines “public safety” itself.

Yet the measure’s central condition—that Oakland maintain at least 700 sworn police officers to receive the tax revenue—was immediately waived after the City declared a state of “fiscal necessity.” Like other recent parcel-tax measures, Measure NN contains an exception clause allowing the city to continue collecting funds even when it does not meet the measure’s requirements — in this case, a failure to meet the staffing threshold. The result is that parcel taxes have become a funding mechanism that gives the city broad discretion to bypass the very conditions voters were told would safeguard accountability.

At the heart of Measure NN is the Oakland Public Safety Planning and Oversight Commission (OPSPOC), a five-member body appointed by the mayor that now sits at the center of Oakland’s public-safety debate.

OPSPOC is tasked with writing the city’s next four-year safety plan, setting spending priorities across departments, and even recommending the number of officers required to collect the tax. As the commission begins to exercise its authority, Oakland faces a new governance reality: a small group of unelected residents will now shape the city’s blueprint for crime reduction, prevention, and policing.

Staffing minimums versus fiscal flexibility

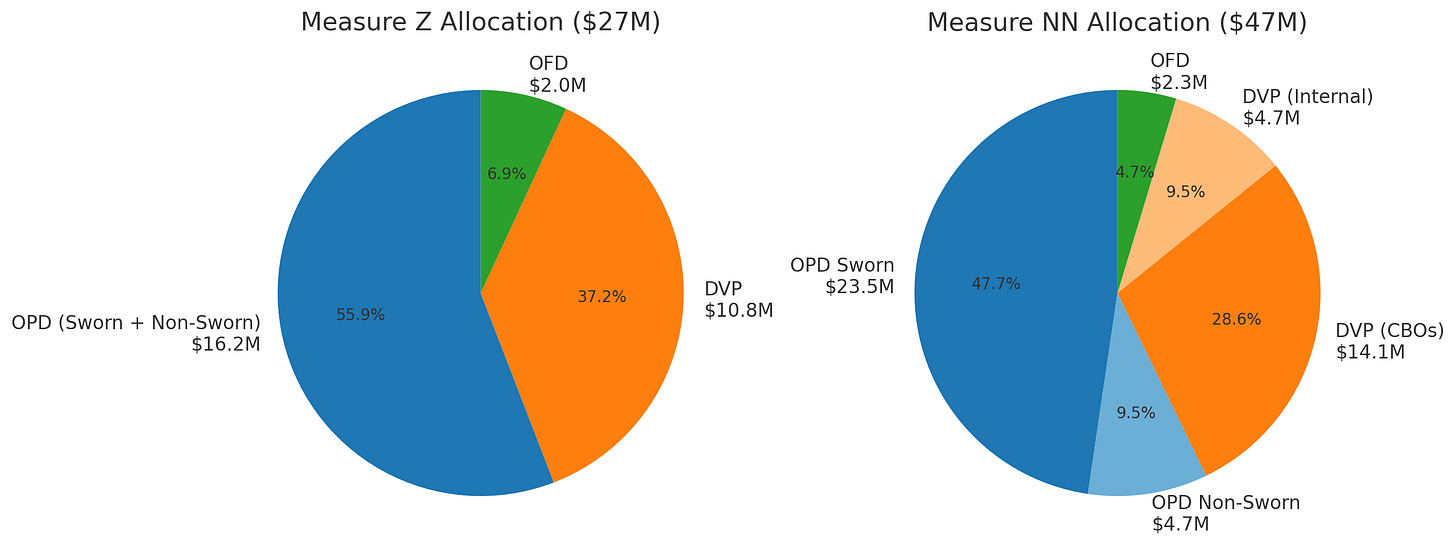

More than 70% of voters approved Measure NN, a parcel tax expected to generate over $45 million annually for public safety. The measure replaced Measure Z, which raised about $27 million a year during its decade in effect.

Both measures included a minimum police staffing requirement: Measure Z set the threshold at 678 sworn officers, while Measure NN raised it to 700. These provisions were designed to link parcel tax revenue to maintaining adequate police staffing levels.

However, each measure also included an exception clause allowing the City to suspend the staffing rule during times of financial necessity. That clause has been invoked under both measures, meaning tax collection continues even when sworn staffing falls below the specified threshold.

In effect, the staffing floor now serves as a guideline rather than a binding condition, a tension that underscores why OPSPOC’s role is so consequential. With the staffing rule effectively flexible, the commission now becomes the arena where questions of “adequate staffing” and “public-safety priorities” are debated and decided.

The architects of Measure NN

Measure NN was backed by Oaklanders Together, a coalition of businesses, labor unions, nonprofits, and firefighters. The coalition emphasized the measure’s “strict accountability requirements” to ensure funds were spent as intended.

David Kakashiba, a key architect of the measure and member of the Oakland Violence Reduction Community Coalition, stated:

“We’re…the people..who know what the people of Oakland actually think.” (OPSPOC meeting, April 28, 2025).

Kakashiba and several others involved in drafting Measure NN previously served on the 2020–2021 Reimagining Public Safety Task Force, which sought to shift resources toward alternative responses and reduce the Oakland Police Department (OPD) budget by 50%. Supporters said the new commission would do more than review spending; it would create a data-driven safety strategy across departments. They argued that while the previous oversight model met audit standards, it never proved whether millions in public funds actually reduced violence. OPSPOC, they said, would finally make prevention measurable with coordination citywide.

That ambition drew skepticism from longtime community members. Community activist Assata Olugbala questioned the process:

“Well, how do you get this privilege [of working on Measure Y, Z and NN]? Because Measure Z was a citizen-sponsored initiative. All of a sudden, the city just dropped it and gave it to these privileged people to come up with the Measure NN. I don’t know how that happened. I don’t know why the city decided not to take responsibility for continuing Measure Z.” (OPSPOC meeting, June 16, 2025)

New commission’s expansive powers under Measure NN

Measure NN established a new civilian body, the Oakland Public Safety Planning and Oversight Commission (OPSPOC), composed of five mayor-appointed volunteers with expertise in areas such as criminal justice and public health. At least one commissioner must have law enforcement or academic expertise in policing.

Prior to the election, analysis of Measure NN by the City Attorney and other groups highlighted that this new commission would have similar oversight requirements to Measure Z. In that case funds were overseen by a civilian oversight commission (Public Safety and Services Violence Prevention Oversight Commission) which reviewed financial audits and performance evaluations.

However, OPSPOC is given powers far beyond oversight: it decides how funds are allocated across departments, develops two four-year Community Violence Reduction Plans, and can recommend changes to police staffing levels that affect tax collection.

A citywide mandate

The Community Violence Reduction Plan extends beyond departments directly funded by Measure NN. At OPSPOC’s first meeting, Deputy City Administrator Joe DeVries told commissioners:

“You are leaders, and your role is to tell the city, is to give us your best advice on how we should spend this funding..Your recommendations on policy could absolutely touch other departments.

Kakashiba reinforced this scope:

“The plan like I said is for the entire city, it’s not just for Measure NN, it’s actually the city’s public safety strategy.”

Commission Chair Yoana Tchoukleva added:

“So, in a way, it [the commission] has a ton of power, and then we can tell OPD or another department, use this strategy, or use that strategy.”

According to DeVries, the plan serves as a “roadmap that [the] City Council will adopt and that our departments will implement.” Under Measure NN, the city council can accept or reject the plan but cannot amend it.

Anne Marks, another coalition member, explained:

“So they can make suggestions and say, you know, come back to you and reconsider, but they can’t actually change it and that’s the city’s plan. So it’s a pretty awesome responsibility.”

OPSPOC presses OPD over spending and staffing

The commission’s main focus has been to question the spending plan of the Oakland Police Department (OPD), the largest beneficiary of Measure NN funds. The commission has sent OPD written questions, which focus on staffing shortages, overtime and rental car expenses. Their questions often referenced a union-backed analysis featured in Oaklandside that criticized police overtime and questioned links between staffing and crime.

OPD cited findings from a 2024 staffing study commissioned by city council, which analyzed workload, overtime trends, and national benchmarks. The report concluded that Oakland requires approximately 877 sworn officers to meet baseline service demands and linked chronic understaffing to rising overtime costs and operational strain. With only about 640 officers and the traffic unit already disbanded, OPD warned that further reductions would deepen the crisis. Despite these findings, OPSPOC members continued to press the department for additional justification of its spending and staffing plans.

Vice Chair Julia Owens said,

“These answers…it’s not responsive and it’s something that we need to know to make an informed plan”

OPD Deputy Chief Anthony Tedesco later replied:

“I wasn’t trying to avoid the question. I was really highlighting to you that the staffing situation is at crisis level for the police department and that many, many, many things, almost everything is exceeding bandwidth.”

OPSPOC’s discussions frequently return to the measure’s 700-officer staffing reference point. Yet because the requirement can be waived during financial shortfalls, the figure now functions more as a planning benchmark than a fixed legal standard, and is a recurring source of debate in how both the commission and the department define “adequate” staffing under Measure NN.

The struggle to rebuild Oakland’s police ranks

The 2025–2027 city budget initially funded six police academies over two years, but low recruitment and high attrition meant no net staffing gains. The city council later reduced the total to five academies with larger class sizes.

Officer recruitment was also a focus of the new budget, with $220,000 allocated for recruitment efforts. Mayor Barbara Lee, in her remarks to OPSPOC, said that she was taking the lead on a recruitment effort and collaborating with OPD (OPSPOC meeting, June 16, 2025). As mayor Lee said:

“This is a big deal for myself with Reverend Damita [Davis-Howard] as my public safety chief in my office. And just know that we want to meet all of the requirements of Measure NN. And we are going to do everything we can do with you to meet those requirements. But no one says it’s easy, because we have, as you know, a budget crisis.”

OPSPOC commissioner Billy Dixon criticized OPD, claiming lack of a clear recruitment plan:

“we’re doing this again and again, and every time we come, we get, we meet with the same resistance…give us what you’re going to do to raise the numbers, because three, because to be real, four academies is not enough”

Ultimately, the mayor and city council, not OPD, control academy funding and recruitment decisions.

How OPSPOC’s expanding role Is testing city departments

OPSPOC must finalize its first citywide Community Violence Reduction Plan before fiscal year 2026–27, but departments had already prepared budgets before the commission existed, creating friction. Director of the Department of Violence Prevention, Dr. Holly Joshi described the dilemma:

“We understood that you all would be responsible for a strategic plan. And we didn’t want to go through an RFP process.”

She noted delays forced her department to issue one-year contract extensions instead of multi-year community-based organization (CBO) agreements, leading to temporary program cuts and public criticism.

OPSPOC later announced plans for a community forum to “hear what works on the ground.” However, after public comment, commissioner Dixon told CBOs:

“So what I need is some statistics from the CBOs showing what you did, how you did it, why you did it, because …you may not be the CBO for us.”

Chair Tchoukleva clarified that OPSPOC does not select CBOs, stating procurement decisions belong to the city. The exchange illustrated confusion over the commission’s role. That overlap between planning and budgeting has left city departments unsure who’s truly in charge

OPSPOC’s push to undo a city contract

OPSPOC also challenged OPD’s proposed use of Measure NN funds for rental vehicles, despite a city council-approved five-year contract with Enterprise funded through the General Fund and Measure NN.

Commissioners have repeatedly questioned OPD representatives about the use of rental cars, and whether they would be used for purposes out of the scope of Measure NN. They have asked for audits of usage, maintenance downtime, and tracking. Deputy Chief Tedesco agreed to look into it, but also replied:

“You’re welcome to disagree, but I can report which units fall under Measure NN—it’s CRO, Ceasefire, Human Trafficking, and some patrol sections.” (OPSPOC meeting, September 22, 2025)

This assessment aligned with OPD’s report to city council, yet OPSPOC’s position could override previously approved funding, potentially nullifying an existing contract. If OPSPOC rescinds funding for a contract already approved by city council, it could trigger legal or budgetary conflicts within city hall and potentially costly disputes with vendors for breach of contract.

The rise of Oakland’s most powerful commission

OPSPOC’s four current commissioners now oversee both Oakland’s citywide public safety strategy and over $45 million in annual parcel tax funds. The commission was described as a “citizen-led body of neighbors and experts, not politicians,” yet its scope rivals that of major city departments. The fifth commissioner seat, reserved for a person with law enforcement experience, is now vacant due to the recent resignation of commissioner Eric Karsseboom, a former OPD officer (OPSPOC meeting September 22, 2025). Commissioner Dixon previously served on the Measure Z oversight board but quit because “it got too political,” promising to step down again if the same happened here (OPSPOC meeting, April 28, 2025).

The current commissioners lack prior experience developing large-scale policy frameworks. They now plan to spend the measure’s funds to hire an external consultant to conduct research, facilitate focus groups, and draft the city’s first Community Violence Reduction Plan. (OPSPOC meeting, June 16, 2025).

Under Measure NN, the commission’s plan serves as the guiding framework for all city departments on public-safety strategy and resource allocation, leaving the City Council with the power only to accept or reject it. As OPSPOC begins drafting its first citywide blueprint, Oakland will soon see whether this experiment in citizen-driven safety governance can deliver results, or deepen the city’s oversight maze.

The next meeting of the Oakland Public Safety Planning and Oversight Commission is scheduled for 6:00 p.m., Monday, October 20, 2025 at City Hall.

Tags: Perspectives, Police, Public Safety, Violence Prevention, Ballot Measures, Commissions

Great article, Rajni! “we the people” voted for specifics in measure NN, yet it was immediately taken away from “we” and given to a private commission (?) and THEY are going to sub-out what they are incapable of doing!!! Outrageous!

“More than 70% of [Oakland’s] voters” are gullible fools. And they like it that way.