Commentary: Oakland needs a council-manager government — or needs to eliminate ranked-choice voting

A former city council member and mayoral candidate explains why he changed his mind about Oakland's form of government.

BY LOREN TAYLOR

Editor’s note: Oakland Report’s charter reform series is exploring Oakland’s city charter and how it potentially could change — a question that Oakland voters may be asked on the ballot in 2026. We invited former Oakland city council member and mayoral candidate Loren Taylor to offer his perspective on Oakland’s governance model. Future installments will invite counterpoint perspectives from other prominent participants in the charter reform debate.

We didn’t get what we were promised

Oakland’s current “hybrid” governmental structure was sold to voters as a “strong-mayor” system. Former mayor Jerry Brown championed it in the Measure X charter reform initiative, and Oakland voters approved it in 1998.1

But in practice, Oakland’s current governmental structure is neither strong-mayor2 nor council-manager.3

In the current “hybrid” structure, power is divided and accountability is diffused. The result is that no one takes full responsibility when the city fails to deliver on its obligations to provide a safe, clean, efficient, well-run city.

Instead, accountability is a finger-pointing exercise where the mayor blames the council, the council blames the city administrator, and everyone blames the way the government is structured.4

I experienced this dysfunction firsthand when I served on the city council from 2019 to 2023. On multiple occasions during closed sessions, I watched my council colleagues acknowledge hard truths about Oakland’s budget crisis, but then fail to do anything about it.

In one particularly telling closed session during the pandemic era, nearly every council member acknowledged that we faced dire financial straits with limited options. We all understood that concessions from major stakeholders — including labor partners — were mathematically necessary to avoid insolvency.

Yet when it came time to vote to merely initiate conversations with labor, a majority of my colleagues abstained. Unwilling to be on the record voting in favor or against, they opted not to vote at all — a political tactic to avoid upsetting powerful interest groups or other political allies.

It reinforced how Oakland’s current “hybrid” system of government allows elected officials to dodge tough decisions, and inhibits the political courage Oakland desperately needs to solve its toughest problems.

Why I originally supported the “strong-mayor” form of government

When I first ran for Oakland City Council in 2018, I believed Oakland needed a true “strong-mayor” form of government.

My initial reasoning for supporting a strong-mayor form of government was straightforward: give Oakland voters direct democratic control over a single executive who can be held accountable for the city’s direction.

Like the federal and state systems, a strong-mayor government would create three clear branches—legislative, executive, judicial—with distinct roles and responsibilities, and integral checks and balances.

In the strong-mayor model, the mayor serves as the city’s chief executive officer (CEO) responsible for the city’s day-to-day operations, with the support of professional administrative staff. The council serves as a policy-setting legislative body. The mayor sometimes also holds veto power over legislation.

This structure is designed to provide citywide perspective and vision for city operations that is directly accountable to voters.

The most common alternative, a council-manager system — in which the mayor serves as the council chair and an appointed professional city manager serves as CEO — seemed to dilute democratic accountability.

In a council-manager system, if the city manager performs poorly or takes actions residents oppose, citizens would need to convince a majority of council members to take corrective action. That seemed to be a much higher political bar than convincing one elected official: their mayor.

Back then, I believed the difficulty of unifying a majority of council members to take decisive action to be a greater risk to Oakland’s future than giving an elected mayor strong executive power.

Now, after four years serving on the city council representing District 6 and running for mayor twice, I’ve reached a different conclusion:

Unless Oakland eliminates ranked-choice voting, or modifies it to restore runoff elections, the city should return to a council-manager form of government.

Video clip 1: “Local Government That Works: The Council-Manager Form of Government.” International City/County Management Association, June 18, 2019. (YouTube / ICMA)

Ranked-choice voting changed the equation — and changed my mind about strong-mayor government

What changed my thinking about strong-mayor government wasn’t a shift in Oakland’s problems. It was recognizing a structural incompatibility that I’d underestimated (and that Jerry Brown never anticipated): ranked-choice voting.

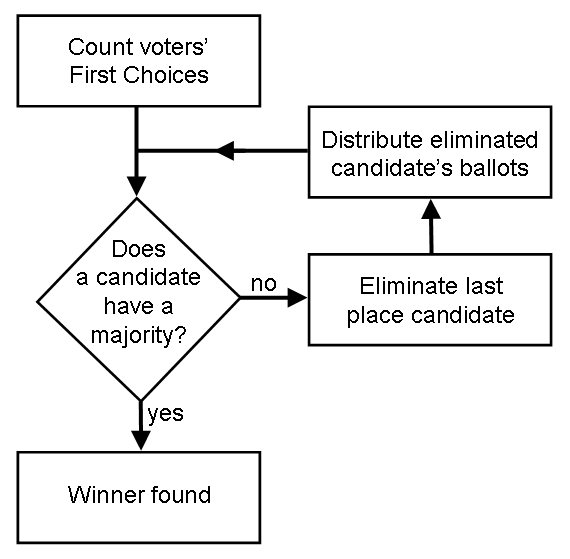

Oakland’s ranked-choice voting (RCV) system is designed to elect so-called “compromise candidates.” In some respects, this means that RCV tends to elect the candidates most voters would settle for, not necessarily who most voters would choose above all others to lead them — or who voters would choose in a separate runoff between two finalist candidates.

This “compromise” isn’t a bug; it’s the system’s central feature. By redistributing second and third-place votes when no candidate reaches a majority of first-place support, RCV mathematically favors compromise over competitive excellence.

Ranked-choice voting is designed to elect candidates “more likely to be ranked as second or third choice”

Ranked-choice voting advocates are candid about the system’s purpose: it’s explicitly designed to elect compromise candidates rather than those with the strongest initial support. This isn’t a bug—it’s a feature that RCV supporters tout often.

For example, the University of Chicago’s Center for Effective Government stated that “RCV particularly favors moderate candidates, because these candidates tend to be the second choice or compromise candidate of other candidates’ supporters.”5

The American Bar Association concluded that the RCV system tends to elect “more consensus building candidates,” who are “more likely to be ranked as a second or third choice by a wider array of voters.”6

These “compromise candidates,” elected through ranked-choice vote redistributions instead of by majority in first-round or runoff votes, often deliberately strengthen their electability in the RCV system by avoiding tough stands.

Traditional runoffs allow additional vetting, public debate, and scrutiny of the top two finalists from among a crowded field

Consider the 2022 mayoral election, where I ultimately placed second after nine rounds of ranked-choice eliminations and vote transfers.

In that election, I received the highest percentage of first-choice votes (33.7 percent) among a field of 10 candidates. Sheng Thao received the second-highest percentage of first-choice votes (31.79 percent). Thao ultimately won after multiple rounds of automated vote transfers, prevailing by fewer than 700 votes – a 0.6 percent difference.7

My point isn’t to relitigate the 2022 election, but to illustrate that RCV worked exactly as designed. It eliminated a competitive element that a traditional runoff would have allowed. Additional vetting, public debate, and scrutiny of the top two finalists, followed by a straightforward runoff vote would have produced a more decisive winner with a clearer mandate, rather than a compromise candidate who emerged through automated vote redistribution algorithms.

Unfortunately for Oakland, former mayor Thao was indicted by the FBI on federal bribery and corruption charges while in office,8 then recalled by 60.62 percent of Oakland voters,9 and now awaits trial. During her brief tenure, she contributed to a $360 million budget deficit,10 and controversially fired a popular police chief.11

Had former mayor Thao taken office in a governmental structure with true “strong-mayor” powers, she would have had even greater opportunities to become involved in activities like the ones that led to her indictment and recall.

With ranked-choice voting, governmental structure needs clear roles and strong checks and balances

Engineers don’t design bridges to handle average traffic—they design for the maximum possible load. The city’s governmental structure must be designed for the worst case it will encounter, not the best.

A strong-mayor system paired with Oakland’s current version of ranked-choice voting is a recipe for possible disaster that Oaklanders can ill afford. We have seen the substantial damage to Oakland’s reputation, budget, and trust that is possible in just two years with Oakland’s current “hybrid” government combined with ranked-choice voting. A true strong-mayor government could compound that damage exponentially.

Ranked-choice voting systematically selects for compromise candidates who avoid taking clear positions; who build coalitions through ambiguity rather than vision; and who often aim to win by being the least objectionable option rather than the most transparent, compelling, or qualified one.

These are precisely the candidates who I believe should not have concentrated executive power, absent a clear mandate from a majority of voters in a straightforward election or runoff.

The potential benefits of giving strong-mayor powers to competent, successful mayors don’t justify the risk of giving those same powers to even one severely flawed mayor who could use those powers to make catastrophic unilateral decisions. Especially when the successful, competent mayors with clear mandates from majorities of voters can still be effective under a council-manager system.

The “mandate exception” — and why it doesn’t justify the risk

Some may point to current mayor Barbara Lee (who received 50.03 percent of the first-round votes in 2025)12 or former mayor Libby Schaaf (who received 53.27 percent of first-round votes in 2018)13 as evidence that ranked-choice voting can produce capable leaders.

But there’s a crucial distinction:

When a candidate receives over 50 percent of first-place votes, ranked-choice voting becomes irrelevant.

Lee and Schaaf won outright majorities in a single round. Their mandates existed despite ranked-choice voting, not because of it.

The question that follows is: What happens the rest of the time?

In Oakland’s five mayoral elections since RCV was implemented in 2010, only two resulted in outright majorities in the first round of RCV voting — Libby Schaaf in 2018 and Barbara Lee in 2025.

The other three elections resulted in no clear winner in the first round — Jean Quan in 2010 (who received 24.47 percent of votes in the first round),14 Libby Schaaf in 2014 (29.48 percent in the first round),15 and Sheng Thao in 2022 (31.79 percent in the first round).16 The lack of clear majorities in these elections led to multiple rounds of automated ranked-choice vote redistribution until majorities were tabulated.

Even if it only happens once or twice per decade, is concentrating executive power in the hands of someone elected by less than a third of voters on their first choice worth the risk?

See this related article:

Why council-manager government is a better choice — if a city also has ranked-choice voting

Unless we’re willing to eliminate ranked-choice voting or modify it to restore runoff elections between the top two candidates, Oakland needs a governmental structure that assumes compromise candidates will win ranked-choice elections, and builds appropriate guardrails.

A council-manager system provides critical safeguards in this respect:

Distributed decision-making (checks and balances): Major decisions require buy-in from multiple elected officials, making it harder for any single weak, incompetent or corrupt leader to unilaterally drive unsound decisions.

Professional management: A city manager is hired based on qualifications and executive experience, not political coalition-building. This professional brings continuity and expertise that compromise candidates often lack.

Built-in accountability: While it takes more effort to move a majority of council members than it does one mayor, that’s actually a feature when ranked-choice voting is selecting our leaders. It prevents hasty, poorly-considered actions while maintaining democratic oversight through the council’s hiring and firing authority over the city manager.

Political cover for tough but necessary decisions: Council members as a group can direct a city manager to make unpopular but necessary decisions — like demanding vendor concessions or restructuring labor agreements — lessening the political impact and serving as a buffer against outside influences on each individual council member.

This isn’t a perfect solution. A council-manager system with ranked-choice voting still occasionally elects compromise candidates for mayor and city council. But requiring checks and balances among multiple elected officials would help prevent the worst outcomes — such as the catastrophic unilateral decisions that a single compromise candidate with strong-mayor powers could make.

A price I’m willing to pay

I want to be clear: I have not ruled out running for Oakland mayor again in the future. If that happens, advocating for a council-manager instead of a strong-mayor system would weaken the executive power of the position I’d be seeking. A professional city manager would handle day-to-day operations. The mayor would serve primarily as council chair and the public face of city government — important roles, but with far less executive power than a true strong-mayor.

But I believe that Oakland needs a governance structure that protects against the worst outcomes our electoral system can produce. After four years on the council and two mayoral campaigns, I’ve learned that what’s best for me personally or politically isn’t always what’s best for Oakland.

That’s the essence of public service: doing what’s best for the city we serve, even when it’s not what’s best for our own political ambitions.

The path forward

I’m under no illusions about the difficulty of the charter reform conversation. I once advocated for strong-mayor powers. I understand the appeal of direct political accountability for the city’s chief executive, of giving voters the power to elect someone with real authority to fix Oakland’s problems.

But I’ve learned that good governance isn’t just about the powers we grant. It’s about how those powers interact with our electoral system.

Oakland’s ranked-choice voting has been in place since 2010 and has survived multiple challenges.17 Any charter reform to change that electoral process must account for that reality — it would be an uphill battle.

Changing Oakland’s governmental structure may be more achievable. We cannot build a governance structure that assumes we’ll elect the strongest possible candidates when our electoral system is explicitly designed to elect the most broadly acceptable “compromise” candidates.

That’s not pessimism. It’s a fundamental tenet of engineering, whether designing a technological system or a political one: you design systems for the conditions you have, not the conditions you wish existed.

See this related article:

Changing to a council-manager form of government won’t solve all of Oakland’s problems. But it will create the institutional safeguards we need when ranked-choice voting produces compromise candidates who lack a clear mandate from a majority of voters in straightforward first-round or runoff votes.

A council-manager form of government can give the city a long-term, high-caliber professional manager who will deliver a thriving city while also protecting the city from malpractice by officeholders who lack the vision, experience, or political courage to lead Oakland through our multiple ongoing crises.

Oakland deserves an accountable government that works. That’s why Oakland should return to a council-manager model — unless we simultaneously eliminate ranked-choice voting or modify it to restore runoff elections. Not because the strong-mayor form of government is wrong in theory, but because it’s too risky in practice given how Oakland currently elects its leaders.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Loren Taylor is a third-generation Oaklander who brings his background as an engineer, management consultant, and community leader to improve outcomes in communities across the country. He served on the Oakland City Council representing District 6 from 2019-2023, and is an elected delegate to the Alameda County Democratic Central Committee.

Loren founded Empower Oakland, a civic engagement and community empowerment organization, and currently leads Custom Taylored Solutions, LLC, a social impact consulting firm where he guides mission-driven for-profits, nonprofits, and government agencies in better delivering on their visions for social change.

The views expressed in our Commentaries do not necessarily reflect the editorial views of Oakland Report or its contributing writers

DelVecchio, Rick and Debra Levi Holtz. “Election ‘98 Coverage: Oakland Measure X.” San Francisco Chronicle (via SFGate), Nov. 4, 1998. https://www.sfgate.com/politics/article/Election-98-Coverage-Oakland-Measure-X-2980993.php

Wikipedia contributors. “Mayor–council government.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, accessed Jan. 9, 2026. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayor%E2%80%93council_government

Wikipedia contributors. “Council–manager government.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, accessed Jan. 9, 2026. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Council%E2%80%93manager_government

Falk, Steven, et al. “Commentary: Oakland Should Return to the Model City Charter.” Oakland Report, Dec. 22, 2025. https://www.oaklandreport.org/i/182267479/oaklands-current-governmental-structure

Eggers, Andrew and Laurent Bouton. “Democracy Reform Primer Series: Ranked-Choice Voting.” The University of Chicago Center for Effective Government, Apr. 30, 2024. https://effectivegov.uchicago.edu/primers/ranked-choice-voting

Dowling, Eveline and Caroline Tolbert. “What We Know About Ranked Choice Voting.” American Bar Association, Mar. 06, 2025. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_interest/election_law/american-democracy/our-work/what-we-know-about-ranked-choice-voting-2025/

Alameda County Registrar of Voters. “Ranked Choice Voting Results: General Election - 11/08/2022; Mayor - Oakland (RCV).” Alameda County Registrar of Voters, Dec. 8, 2022. https://www.alamedacountyca.gov/rovresults/rcv/248/rcvresults.htm?race=Oakland%2F001-Mayor

U.S. Attorney’s Office, Northern District of California. “Former Oakland Mayor Sheng Thao, Thao’s Longtime Partner, And Two Local Businessmen Charged With Bribery Offenses,” U.S. Attorney’s Office, Northern District of California, Jan. 17, 2025. https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndca/pr/former-oakland-mayor-sheng-thao-thaos-longtime-partner-and-two-local-businessmen

Alameda County Registrar of Voters, “General Election - November 05, 2024 - Certified Final Results - Recall Sheng Thao.” Alameda County Registrar of Voters, Dec. 5, 2024. https://alamedacountyca.gov/rovresults/252/

Fitzgerald Rodriguez, Joe. “Budget Deep Dive: Unpacking Oakland’s $360 Million Shortfall.” KQED, Aug. 9, 2023. https://www.kqed.org/news/11957562/budget-deep-dive-unpacking-oaklands-360-million-shortfall

Bay City News Service. “Oakland Mayor Sheng Thao Fires Police Chief LeRonne Armstrong,” SFGate, February 15, 2023. https://www.sfgate.com/news/bayarea/article/mayor-thao-fires-police-chief-leronne-armstrong-17787153.php

Alameda County Registrar of Voters. “Ranked Choice Voting Results: City of Oakland Special Municipal Election - April 15, 2025, Mayor, Short Term - Oakland (RCV). “ Alameda County Registrar of Voters, May 2, 2025. https://alamedacountyca.gov/rovresults/rcv/257/rcvresults.htm?race=Oakland%2F001-Mayor

Alameda County Registrar of Voters. “Ranked-Choice Voting Accumulated Results - Mayor - Oakland.” Alameda County Registrar of Voters, Dec. 6, 2018. https://www.alamedacountyca.gov/rovresults/rcv/236/rcvresults_100100.htm

Alameda County Registrar of Voters. “Ranked Choice Voting Results - Pass Report; Contest: Mayor - Oakland.” Alameda County Registrar of Voters, Nov. 2, 2010. https://acvote.alamedacountyca.gov/acvote-assets/pdf/elections/2010/11022010/results/rcv/oakland/mayor/november-2-2010-pass-report-oakland-mayor.pdf

Alameda County Registrar of Voters. “Ranked Choice Voting Results - Pass Report; Contest: Mayor - Oakland.” Alameda County Registrar of Voters, Nov. 4, 2014. https://acvote.alamedacountyca.gov/acvote-assets/pdf/elections/2014/11042014/results/rcv/oakland/mayor/nov-4-2014-pass-report-mayor-oakland.pdf

Alameda County Registrar of Voters. “Ranked Choice Voting Results: General Election - 11/08/2022; Mayor - Oakland (RCV).” Alameda County Registrar of Voters, Dec. 8, 2022. https://alamedacountyca.gov/rovresults/rcv/248/rcvresults.htm?race=Oakland%2F001-Mayor

Mukherjee, Shomik. “Amid Expansion Elsewhere, Oakland’s Ranked Choice Voting Struggles.” Governing (via Bay City News Service), Oct. 21, 2024. https://www.governing.com/politics/amid-expansion-elsewhere-oaklands-ranked-choice-voting-struggles

Loren, really appreciate how you draw out the deeper dependencies in the governance system --- particularly when you get a bad mayor in a strong mayor system.

Reform needs to consider all those linkages and possibilities in designing a future governance. Otherwise you might simply move the brick wall to a new spot, or open up a new trap.

Charter reform seems like a good idea, but if you don't address the broader flaws in our system, it might lead to such a trap. These flaws amplify each other right now (in addition to our hybrid system and RCV).

Few are willing to say it because of the fear of political or social backlash, but I'll say it. It is my hope that these issues can also be tackled through a reform process.

1. Our city commission structure often places people without expertise, without sufficient time/resource, without accountability, and often with narrow or conflicted interests in positions of authority over our elected leaders through explicit veto power, or the power to delay decisions.

2. Closed-door negotiations between public unions and the city is a deep conflict of interest. Unions receive nearly 1-1.7% of the salaries of city employees (which amounts to more than $6M a year of taxpayer money), some of which is used to elect the politicians that approve those salaries.

--> Over $4M spent on political activity by these unions based in Oakland. (See here for filing docs summary: https://gemini.google.com/share/282e308acf84, and for example the SEIU filing, here: https://olmsapps.dol.gov/query/orgReport.do?rptId=862170&rptForm=LM2Form)

--> Effectively, unions are a city contractor allowed to contribute to candidates and then negotiate with them behind closed doors. Greater transparency is critical.

3. There is no state or other external requirement for the fiscal transparency that is essential to good governance. As we have seen recently, the city can delay financial reporting (or skip it) at well -- leaving the council in the dark and with limited options when things get tough.

4. There seems to be a notion that a city job is lifetime employment, regardless of employee performance, or of city needs. There are some amazing talents in the City of Oakland, and some deeply committed employees. But like every private or public organization ever, there are employees who don't perform.

--> If talented folks are not advanced based on merit, or if their every effort at service improvement is crushed by others' apathy, they get frustrated and leave. A merit based culture starts a the top -- and "the top" is selected and held accountable by the system of governance.

--> If the city cannot contract its workforce when needs change for finances change, we are doomed to wasteful, unsustainable governance.

5. There is a lack of any real accountability for long-term decisions -- e.g. spending decisions on contracts or pensions that won't impact current elected, but could sink the city years in the future. Whether it be road repairs (and $Ms in lawsuit payments for the lack thereof), or pensions, or broken contracts leading to decades-long lawsuits, we've seen those decisions play out repeatedly over the past 20 years. Unclear how to solve this, but those past decisions by electeds -- who never felt their impact -- are a large part of our current problems.

There were three of us that sat on the charter review committee that presented a dissension to the majority report. We never should have changed our form of government. It happened primarily because Jerry Brown didn’t want to attend council meetings. As for RCV, I have stopped ranking candidates and now only list one. I am tired of voting for mediocre candidates.