Oakland schools budgeting 101: how Oakland schools are funded

OUSD’s budget crisis is playing out in slow motion in the public eye. Understanding the district's options starts with understanding how OUSD is funded.

Oakland Report is covering the Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) board of education’s efforts to close an over $100 million budget deficit for next school year in an attempt to avoid a slide back into state receivership (See our previous articles here and here).

In this installment, we provide a primer on OUSD’s budget, specifically focusing on how Oakland schools are funded. (You can read our previous primer on OUSD budget governance here.)

Future installments in this series will take a look into where the money goes, the backgrounds of the current board members, the legal and political dynamics shaping their decision-making, and why balancing the budget continues to be such a challenge for OUSD.

Where the money comes from

With this primer, our goal is simple: to support a more informed debate by providing background on how OUSD is funded. There are a few takeaways:

Around half of OUSD’s revenue is unrestricted, meaning that it can be used to cover any expenditures in the budget.

The unrestricted revenue comes overwhelmingly from the state, mostly through a combination of sales and income taxes as well as local property taxes. Tax monies are allocated to school districts through a formula that uses attendance as the key input while providing additional funding for high-needs students.

The other approximately half of OUSD’s revenue is restricted, with state, federal and local funding allocated to specific types of expenditures that were approved through legislation or ballot measures.

Some of the restricted funding is permanent and some is temporary or one-time in nature, with some programs expiring on a given date unless re-approved and some programs or projects that are one-time or time-bound.

See these related articles:

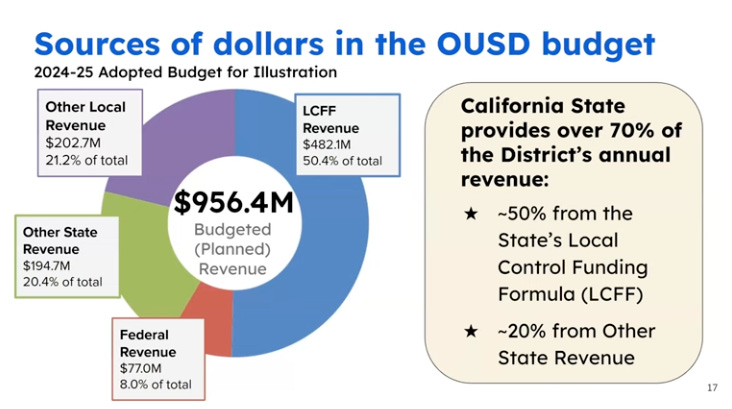

Now, let’s dive into more detail. The diagram below breaks down the sources of revenue for OUSD in the 2024-2025 school year:

State revenue sources

The State of California provides approximately 70% of the revenue to OUSD’s overall budget. State funding is primarily administered by the California Department of Education through the Alameda County Office of Education.

Local Control Funding Formula (~50%)

The Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) accounts for approximately half of OUSD’s budget and around 97% of its unrestricted funds which can be used to cover any expenditure within the district. Financed by property taxes, income and sales taxes, LCFF was adopted in 2013 to replace a patchwork system consisting of dozens of state grants.

The intent with LCFF is to streamline funding into a simple formula that empowers local school boards and benefits districts with more high-needs students.

The formula1 starts with a fixed amount per student, the base grant, which it then supplements by 20% for low–income students, English learners, and foster youth. To support districts with concentrated poverty and/or many high-needs students, it adds an additional 65% of the base grant for each student above 55% of district enrollment.

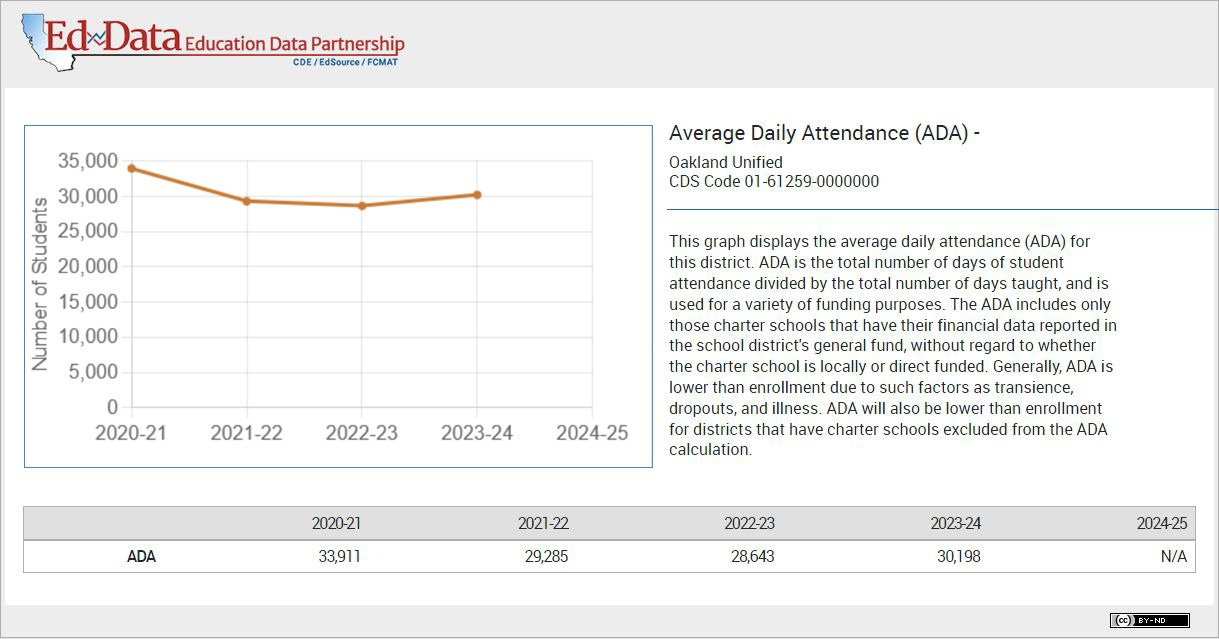

Average Daily Attendance is a key input

Average daily attendance (ADA) corresponds to how many total days students attend as a percentage of the total instructional days. It is the key input that determines the amount of LCFF revenue OUSD receives. This creates a strong incentive for OUSD to maximize not only enrollment, but also the number of days that students attend OUSD schools – maximizing average daily attendance is a powerful lever available to OUSD to increase revenue.

When parents choose not to send their children to OUSD, their property taxes still fund the schools, but property taxes represent a minority of LCFF funding. Since their child is not counted towards ADA, no additional state income or sales taxes are allocated to the district.

A significant factor in attendance is that approximately 24% of OUSD students are chronically absent, meaning they miss more than 10% of the school days in a given year. When students are chronically absent, less revenue flows to OUSD under the formula. For the most recent school year to date, the attendance rate is 92%,2 which means OUSD only received 92% of its potential funds under the LCFF. These figures have been improving in recent years, but still result in OUSD receiving less than the maximum possible amount of revenue.

Local Control and Accountability Plan provides framework

The LCFF also comes with a framework for school district accountability, known as the Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP).3 Each year, the district must set goals and metrics aligned to state priorities, including student achievement, engagement, and exposure to a broad curriculum. In doing so, the school board must engage the community, giving parents, students and teachers an opportunity to offer feedback at public hearings. The entire process, including goal setting and measurement against success metrics, is overseen by the Alameda County Office of Education.

Other state revenue (~20%)

In addition to the state revenue distributed through the LCFF, the state contributes another approximately 20% of OUSD’s budget through funding that is restricted to specific purposes, such as special education and arts and music programs.

The main revenue mechanism for special education is AB 602, which was passed in 1998. Money is allocated to groups of school districts that pool special education resources and services, and then allocate their funding out to each district based upon the same ADA metrics used under the LCFF. These funds can be used for specialized, credentialed staff as well as speech, occupational and physical therapy services. The funding can also be used to support students with severe disabilities, such as by providing special transportation or instruction at home or in a hospital.

Another example of restricted state funds is Proposition 49, approved by voters in 2002. It established permanent, dedicated state funding for after-school programs serving elementary school students. OUSD received over $9.5 million for the 2024-2025 school year, supporting after school programs at elementary, middle and high schools throughout the city.

Local revenue sources (~21%)

Local revenue provides approximately 21% of the revenue to OUSD’s overall budget. Local revenue comes from a combination of parcel taxes, general obligation bonds, private donations, and fundraising through parent-teacher associations.

Parcel Taxes

There are three main parcel taxes that combined generate over $40 million per year for Oakland schools.4 Each parcel tax has a citizens’ oversight committee that reviews all spending, and is audited annually. Specifically:

Measure G, approved by 79% of Oakland voters in 2008, is a permanent $195 per-parcel tax that collects approximately $20 million per year. By law, Measure G money must benefit Oakland public schools and can only be spent on specified priorities, including retaining qualified teachers, maintaining college prep courses, updating textbooks and materials, keeping class sizes small, continuing after-school academic programs, maintaining school libraries, and providing arts and music programs that enhance achievement. Measure G explicitly cannot fund central office administrator salaries.

Measure G-1 was approved by voters in 2016, is a separate parcel tax of $120 per parcel that collects approximately $12 million per year for 12 years. The Measure G-1 funds are split between raising pay for school-site educators and giving middle school grants for arts, music, and world language programs to improve student retention and campus culture.

Measure H was approved in 2022, and is a $120 per parcel tax that collects approximately $11 million per year for 14 years. These funds are restricted to college & career readiness, including offering real work experience and technical training.

Parcel taxes are only paid by property owners, and there are exemptions for low-income and senior households. Thus, while the entire voting population in Oakland votes on parcel taxes only a subset of residents pay them.

General Obligation Bonds

In addition to parcel taxes, there are three separate general obligation bonds that were placed on the ballot by the OUSD school board and approved by voters over the last 20 years:

Measure B was passed in 2006, and approved OUSD taking on $435 million in debt to fund building repairs and safety. It is paid back through an ad valorem property tax, meaning that the tax is assessed as a percentage of the property’s market value. These funds were largely spent prior to 2019, and there is zero capacity remaining.

Measure J was passed in 2012, and approved $475 million in debt to fund additional repairs, upgrades and modernization of school facilities. From the most recent annual report, it is unclear exactly how much capacity is remaining.5

Measure Y was passed in 2020, authorizing up to $735 million for additional repairs and retrofits. In 2023, the Alameda County Board of Supervisors approved OUSD’s issuance of the first $185 million in bonds under Measure Y, which implies there is roughly $550 million remaining.6

These bonds are repaid through property tax assessments and overseen by citizens oversight commissions and independent auditors.7 In contrast to parcel taxes, the funds are not approved for a specific period of time, but rather until all of the capacity has been used. Under Proposition 39, school bond measures must include specifics on how the money will be used, and cannot be used for administrator or teacher salaries.8

Private revenue sources

Donations

In addition to state and local tax funds, OUSD has also received donations from a number of individuals and organizations over the years. Recent notable donations include approximately $35 million from Salesforce given from 2017 to 2023, with a focus on computer science and STEM expansion, as well as student services to welcome newcomers;9 and $700,000 from Mark Pincus, co-founder of Zynga,10 for technology access for OUSD students.

While philanthropic donations are admirable, these are typically one-time or limited duration grants with specific goals in mind. Once the funds expire, they can leave the district with the challenge of finding new ways to finance the same ongoing needs.

A notable example in Oakland is the Gates Foundation providing more than $40 million in funding for “small schools” in the mid-2000s under the philosophy that if you broke up large, underperforming schools, you could drive better student outcomes.11 The program resulted in OUSD opening dozens of new schools, and while it did generate positive outcomes for a subset of students,12 when Gates moved on to other priorities, it left OUSD with the challenge of how to make the schools financially sustainable for the long-term.

Parent-Teacher Associations (PTAs)

PTAs are organized school by school, and augment state, local and federal funding. These funds can be used for a variety of purposes specified by the PTA, including for things like art instruction, specialized tutors, field trips, or classroom supplies.

PTAs can be helpful resources to support and augment OUSD schools, but are an inconsistent funding stream, with orders of magnitude differences in the amount of giving from school to school that shape student experiences and outcomes at those schools.

There are significant disparities in PTA giving among schools. Schools in wealthier neighbors raise hundreds of thousands of dollars, which in some cases can equate to more than $1,000 per child. By contrast, schools in less wealthy neighborhoods might raise far less.

Federal revenue sources (~8%)

Federal revenue provides approximately 8% of the revenue to OUSD’s overall budget. Federal funds are highly restricted, focus on students with the highest needs, and fall into two basic categories:

Ongoing federal entitlements

These funds are delivered annually based on student characteristics such as income level, English-learner status, and special education needs. These funds supplement, but do not replace state and local spending. A few of the key programs:

Title I: Largest federal source; supports schools with high concentrations of low-income students. Funds literacy and math interventions, tutoring, and school improvement strategies.

Title II: Supports professional development, coaching, and training for teachers and principals.

Title III: Funds English learner programs, newcomer supports, and bilingual/dual-language services.

IDEA: Contributes to special education services, including specialized staff, assessments, and compliance requirements.

Federal nutrition programs: Reimburses the district for providing breakfast, lunch, snacks, and summer meals for high-needs students.

Competitive or program-specific federal grants

These funds are awarded through applications or based on school identification under federal accountability rules. They supplement the core entitlements and often support targeted or innovative programs.

Key programs for OUSD:

21st Century Community Learning Centers (21st CCLC): Funds after-school and summer enrichment at high-poverty schools.

Title IV, Part A (Student Support and Academic Enrichment, “SSAE”): Supports student wellness, enrichment, arts and music, technology access, and school safety.

Comprehensive support and improvement (CSI) and Targeted support and improvement (TSI) funds: Provided to schools identified for Comprehensive or Targeted Support and Improvement under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) to fund school turnaround efforts.

In summary, OUSD’s revenue comes from a variety of local, state and federal sources, and some private sources. Around half of OUSD’s revenue is restricted to specific uses, and around half is discretionary. In recent years, OUSD has supplemented its revenue streams with additional parcel taxes and bonds approved by Oakland voters. The single most powerful lever the district can pull to increase revenue is to increase enrollment and attendance at its schools.

See this related article:

Oakland schools budgeting 101: a primer on OUSD’s budget process

Oakland Report is covering the Oakland Unified School District’s (OUSD’s) board of education’s efforts to close a $115 million near-term budget deficit in an attempt to avoid a slide back into state receivership. In this installment, we provide a primer on OUSD’s budget, specifically focusing on governance and how decisions are made.

If you like our work, please consider donating. We are a volunteer-run, 501(c)(3) charitable nonprofit organization based in beautiful Oakland, California.

Our mission is to make truth more accessible to all Oakland residents through deep investigative reporting and evidence-based analysis of local issues.

Your donation of any amount helps us continue our work to produce articles like this one.

Thank you.

Funding Rates and Information, Fiscal Year 2024–25. California Department of Education, Nov. 14, 2025. https://www.cde.ca.gov/fg/aa/pa/pa2425rates.asp

Press Kit Executive Summary. Oakland Unified School District, Nov. 14, 2025. https://www.ousd.org/presskit/executive-summary

Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP). Oakland Unified School District, Nov. 14, 2025. https://www.ousd.org/about-us/local-control-and-accountability-plan-lcap

Parcel Taxes. Oakland Unified School District, Nov. 14, 2025. https://www.ousd.org/community/parcel-taxes

Measures B, J & Y Independent Citizens’ Bond Oversight Committee Annual Fiscal Year 2023/2024 Report and Fiscal Year 2024/2025 Progress Report. Oakland Unified School District, Nov. 14, 2025. https://resources.finalsite.net/images/v1757955485/ousdorg/fhbwmb0lfeb2svh2odxu/25-1271MeasuresBJandYIndependentCitizensSchoolFacilitiesBondOversightCommittee-2025AnnualReport.pdf

Alameda County Board of Supervisors. Approve The Issuance And Sale Of Not To Exceed $185,000,000 Of General Obligation Bonds On Behalf Of The Oakland Unified School District (The “District”) And Authorize The Execution Of Necessary Documents And Certificates Relating To Said Bonds. October 13, 2023. https://www.acgov.org/board/bos_calendar/documents/DocsAgendaReg_10_24_23/GENERAL%20ADMINISTRATION/Regular%20Calendar/Oakland%20Unified%20School%20District_358708.pdf

OUSD Measures B, J and Y Independent Citizen Bond Oversight Committee (CBOC). Oakland Unified School District, Nov. 14, 2025. https://www.ousd.org/facilities-planning-management/about/facilities-department/district-committees/cboc-committee

California Proposition 39. California Association of Bond Oversight Committees, Nov. 14, 2025. https://www.bondoversight.org/california-proposition-39/

With Another $5.5M in Support, Salesforce Continues Its Partnership with Oakland. Oakland Public Education Fund, Nov. 14, 2025. https://www.oaklandedfund.org/2023/09/14/with-another-5-5m-in-support-salesforce-continues-its-partnership-with-oakland/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Wikipedia contributors. “Mark Pincus.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 31 Oct. 2025. Web. 14 Nov. 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Pincus

30 Years of Transforming Leadership in Public Education. National Equity Project, Nov. 14, 2025. https://www.nationalequityproject.org/about/history

Oakland Unified School District New Small Schools Initiative Evaluation Executive Summary. The School Redesign Network at Stanford University, Nov. 14, 2025. https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/oakland-unified-school-district-new-small-schools-initiative-evaluation_0.pdf

I apologize if this is inappropriate but I couldnt not add this comment in relation to student enrollment and attendance :

"Between October and December 2023, at least 30 transfer requests specifically due to issues related to the conflict were approved. In a later period from March to May 2024, Piedmont district received 261 transfer requests, a jump from 86 during a similar period the previous year, driven in part by Jewish families leaving Oakland."

The conflict above resulted from the October 7th HAMAS attack on Israel. Staff at OUSD held teach-ins and modified curriculum that led to a hostile environment for Jewish students.

Moreover, the California Department of Education's (CDE) investigation determined that OUSD created a "discriminatory environment" for Jewish students in several instances.

Besides OUSD, most of the Oakland City Council, especially Rebecca Kaplan and Nikki "For All of Us" Bas, remained silent when their friends *praised* HAMAS in a city meeting.

Oakland City Hall and OUSD preach diversity and respect but they do not apply that to Jews.

Good to have the basics on OUSD funding. There is a lot of mythology repeated in debates on OUSD - nice to have a level set. For more "color" on OUSD governance and funding, grand jury report is very good IMO https://grandjury.acgov.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/OUSD-Broken-Culture.FR-2.pdf