Give Oaklanders what they want and need: a strong mayor

Former mayor Libby Schaaf lays out the case for a citizens’ initiative to reform Oakland’s charter and put in place a true strong-mayor form of government.

BY LIBBY SCHAAF

Editor’s note: Oakland Report’s charter reform series is exploring Oakland’s city charter and how it potentially could change — a question that Oakland voters may be asked on the ballot in 2026. We invited former Oakland mayor Libby Schaaf to offer her perspective on Oakland’s governance model. Other installments in this series share counterpoint perspectives from other prominent participants in the charter reform debate.

Oaklanders need accountability and transparency in government

During my 24 years working for the City of Oakland — 10 as a political staffer, two as a director at the Port of Oakland, four as a Councilmember, and eight as Mayor — I gained extensive insight into exactly what influences how Oakland’s decisions get made.

My fervent conclusion is this: blurred accountability and low transparency benefit special interests and make it harder for everyday Oaklanders to understand what their government is doing or get their priorities met.

That is why Oakland needs a real strong-mayor form of government.1

Oaklanders would be best served by a strong-mayor government

One of our region’s leading good-government experts, the San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR) issued a 2021 report, Making Government Work: 10 Ways City Governance Can Adapt to Meet the Needs of Oaklanders (“SPUR Report”) that was the result of three years of extensive research and stakeholder interviews. The report concludes that Oaklanders would be best served by replacing our current hybrid form of government with a clearly defined strong-mayor system. The report states:

The recommendations in this section move Oakland from a hybrid council-manager/strong-mayor form of government to a clearly defined strong-mayor form of government. As Oakland has grown in both size and complexity, the need for a more consolidated executive function within government has increased. The people of Oakland expect the mayor to be able to solve citywide problems, and without clearer authority, the mayor is unable to fulfill that expectation.

— from SPUR, Making Government Work, p. 23

Most critically, Oakland’s mayor lacks veto power — not only over legislation, but over budget items, where the most consequential decisions are made.

The SPUR Report — which deserves to be read in full — explains a hard truth: even though Oaklanders think we already have a strong mayor, we do not.

The report’s analysis also shows not only why Oaklanders suffer from the current hybrid system, but also why returning to a council-manager form of government should be rejected:

The hybrid model fails to give the mayor the authority needed to respond to voters and implement an agenda. This means the people of Oakland cannot hold the mayor accountable for the mayor’s performance. Given the size, importance and complexity of a city like Oakland, we don’t believe that returning to a true council-manager form of government is appropriate or desirable. Instead, we recommend moving Oakland toward a strong-mayor system.

— from SPUR, Making Government Work, p. 23

A strong mayor enhances accountability and transparency

Oakland’s mayor is directly elected by the entire city yet lacks the core tools that voters reasonably assume accompany executive responsibility. I agree with the SPUR Report’s recommendation that Oaklanders need their mayor to have a veto over legislation and budget items that could be overridden by a city council supermajority of six votes.

Without veto power:

The mayor is publicly blamed for outcomes she cannot fully control,

Councilmembers can advance spending or policy decisions without bearing responsibility for citywide consequences, and

Voters lack clear visibility between decisions and results.

A mayoral veto does not eliminate checks and balances; it clarifies them. Council authority remains intact through hearings, legislation, and override provisions. But the public gains what democracy requires: a clear, accountable executive who can be judged on performance.

Under a council-manager government, a majority of councilmembers elected from districts other than yours can control decisions, including adopting the budget and hiring and firing the city manager. A strong-mayor is the only system that ensures the buck stops with someone you can vote for or recall.

In today’s media environment, the mayor’s actions are more transparent and scrutinized than any other elected or appointed official. Most Oaklanders do not watch, let alone participate in, long frustrating council meetings. They get civic information through newspapers, television, and social media — outlets that scrutinize the mayor far more closely than any councilmember or city manager.

An Oakland example of mayoral scrutiny is the recall of Mayor Sheng Thao. More than 30,000 Oaklanders signed recall petitions against Thao well before corruption allegations emerged, reflecting broad public awareness and judgment of mayoral performance. Oaklanders will have far more visibility into the decisions and performance of a mayor than of a shifting council majority or unelected city manager.

A mayoral veto promotes collaboration while preserving council power

Since leaving the mayor’s office, I have taught Public Budgeting at UC Berkeley and Northeastern University. One of the textbooks I use lists Oakland as the only strong-mayor city without mayoral veto authority over the budget.2 Even council-manager cities — such as Long Beach and San José — grant their mayors veto powers in various forms.

The SPUR Report argues that a strong mayor will “help Oakland thrive by strengthening a positive culture of collaboration within government and providing tools to elected and appointed officials to solve common problems and better serve the interests of the public.” (SPUR, Making Government Work, p. 5)

This comports with my experience as mayor. For example, the vast majority of Oaklanders want to increase police staffing: 61 percent in the most recent Pulse of Oakland Poll. Yet Oakland’s city council has reduced the mayor’s proposed police funding in nearly every budget in recent years.

The veto is not a weapon; it is a forcing mechanism for earlier negotiation, higher public awareness, and better-designed policy.

A strong mayor improves performance and implementation

Oakland is not short on policy ideas. It is short on the ability — and capacity — to implement them.

Eight legislators passing ordinances, approving major contracts, and hearing from the special interests who disproportionately dominate council meetings is sufficient. Oakland does not need to turn the mayor into a ninth legislator, which is what a council-manager system would do.

Oakland needs one democratically elected executive focused on performance, execution, and results, and who can veto legislation that will stymie it. The City Administrator will be more effective with one elected boss, not nine. It’s worth noting that overall, Oakland’s strong mayors have hired the same caliber of experienced professional managers that would serve under a council-manager system.3

Our federal, state, and most big city governments all separate powers among branches and have an elected chief executive: the legislature makes policy, and the elected executive implements it. Oakland is large, complex, and has big-city challenges; it needs a big-city form of government.

Voters overwhelmingly support a strong mayor

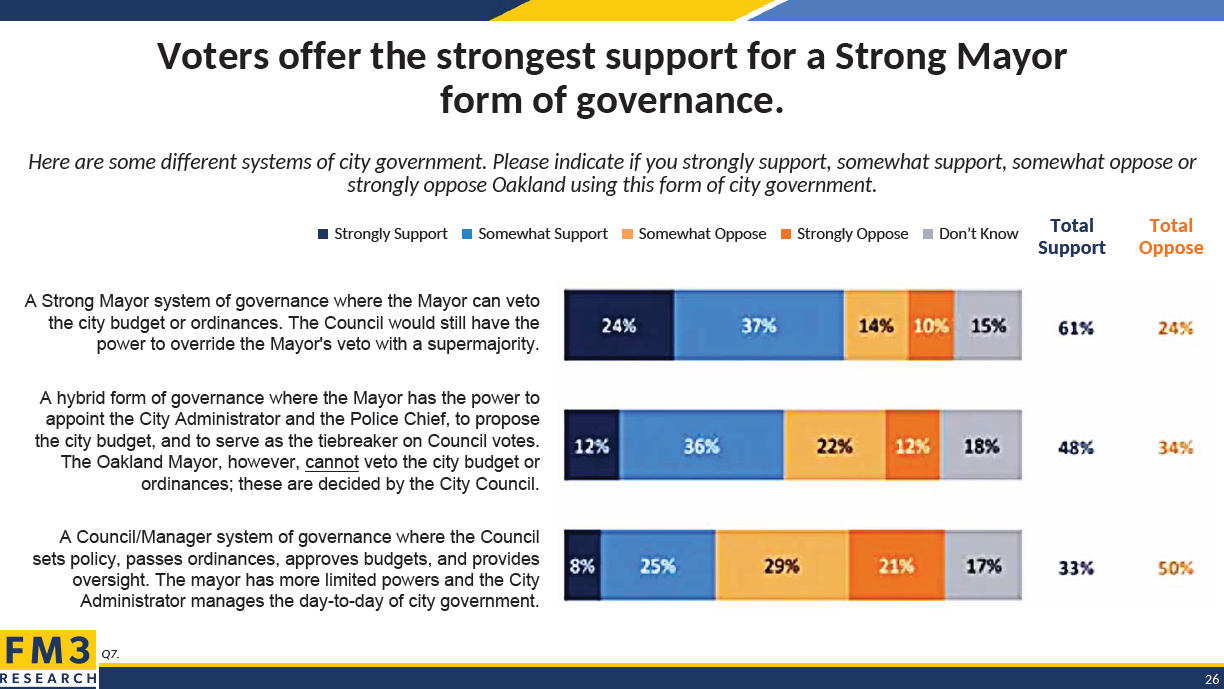

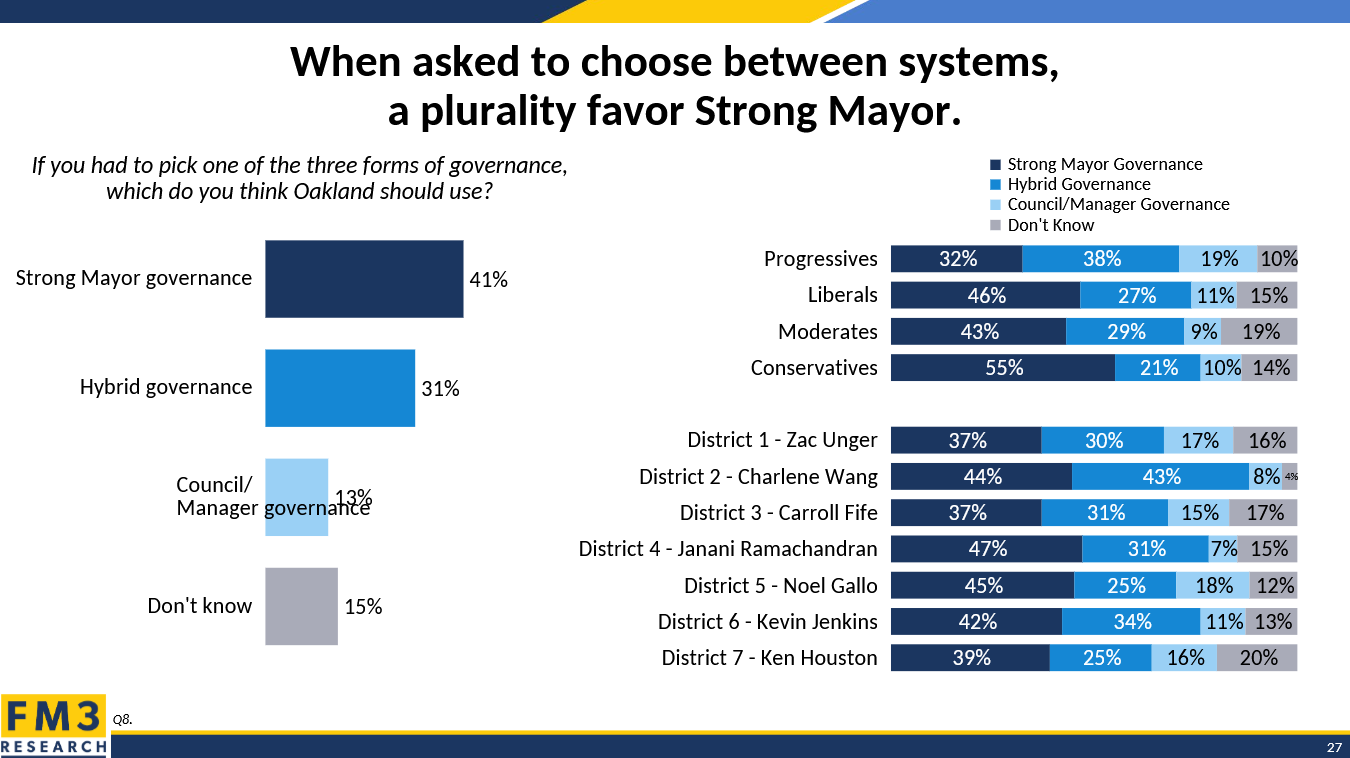

Voters agree. The October 2025 Pulse of Oakland Poll of likely voters found 61 percent support for a strong-mayor form of government. Even Oakland’s current hybrid system received more support than a council-manager model. Half of respondents opposed a council-manager government outright, and only 13 percent said it was their top choice.4

Regardless of one’s personal preferences, these numbers matter. Placing a council-manager measure on the ballot would almost certainly fail, squandering scarce public money and voter trust — resources Oakland cannot afford to waste.

Stronger budget controls

When SPUR released Making Government Work, it urged the City Council to place a charter-reform measure on the 2022 ballot to implement its recommendations. In addition to strong-mayor provisions, SPUR recommended charter revisions to require independently validated balanced budgets and stronger fiscal controls.

The council cherry-picked the recommendations they liked, including a method to increase their own pay, and also included the recommendation for 12-year term limits, which was so popular with voters that the passage of the entire package was nearly guaranteed. They did not advance any of the SPUR Report’s recommendations that would have reduced the city council’s own powers, including:

Give the mayor veto powers,

Constrain the council’s budget discretion with independent fiscal controls, or

Make Oakland a truly strong-mayor city.5

Why a citizen-led initiative is now necessary

2022 was not the first time the Oakland City Council refused to weaken its powers. Jerry Brown placed the original Measure X onto the ballot as a citizens’ initiative in 1998, allowing him to bypass Oakland’s city council.6 The original Measure X gave the mayor the power to suspend legislation, overridable only by a supermajority of six votes — essentially a mayoral veto. That authority was effectively eliminated by the City Council in 2004 when they placed Measure P on the ballot and voters approved it.7

The lesson is straightforward: the City Council will not voluntarily reduce its own power. This pattern is understandable and institutional, not personal.

I commend Mayor Lee for convening a Charter Review Committee to bring attention to this critical issue, but history suggests that Oaklanders who want a true strong-mayor system must organize a citizen-led initiative.

Civic leaders who put Oaklanders’ interests first should begin that work now. It is what voters want — and what Oakland needs to govern effectively into the future.

The views expressed in our Commentaries do not necessarily reflect the editorial views of Oakland Report or its contributing writers

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Libby Schaaf is a life-long Oakland resident, public policy professor, and 50th Mayor of Oakland (2015-2022).

If you like our work, please consider donating to show your support.

We are a 501(c)(3) nonprofit based in beautiful Oakland, California. Our mission is to make truth more accessible to all Oakland residents through deep investigative reporting and evidence-based analysis of local issues.

Your donation of any amount helps us continue our work to produce articles like this one.

Thank you.

I’m assuming readers already understand the three most common forms of local government: council-manager, hybrid, and strong-mayor. For deeper analysis and background on all concepts discussed in this piece, please read SPUR’s Making Government Work report.

Rubin, I.S. “The politics of public budgeting: Getting and spending, borrowing and balancing.” CQ Press, 9th edition, 2020.

The arguable exception is Mayor Ron Dellums hired his long-time political colleague Dan Lindheim who did not have a traditional city administrator’s experience (although many, including me, agree he did a fine job). Permanent city administrators hired by Oakland mayors since 1999 include Robert Bobb, Deborah Edgerly, Deanna Santana, Sabrina Landreth, Ed Reiskin, and Jestin Johnson, all possessing extensive municipal management experience typical of a city manager running a council-manager form of government. Interim Oakland city administrators include seasoned professionals Henry Gardner, John Flores, and Steven Falk.

Oakland Chamber of Commerce. “2025 Pulse of Oakland Poll Results.” Oct. 23, 2025. https://www.oaklandchamber.com/2025-pulse-of-oakland-poll-results/

SPUR 2022 Voter Guide, Oakland Measure X: Governance Reform ; Okoye, Ronak D., Oakland’s Measure X Puts Forth SPUR Ideas (October 25, 2022)

Under California law, municipal ballot measures are placed before voters through either, (1) action of the city’s legislative body, or (2) the voter initiative process. The California Constitution expressly reserves to the electorate the power to propose and adopt laws by initiative (Cal. Const., art. II, § 8), a power that applies to local governments. Consistent with this authority, the City of Oakland’s Municipal Code sets forth procedures for qualifying citywide ballot measures through voter-circulated initiative petitions, while the Oakland City Council retains the authority to place measures on the ballot by council action. See Oakland Mun. Code §§ 3.08.200–3.08.240.

“Under Measure X, the mayor was also given the authority to ‘suspend’ an ordinance (but not veto it) if it was passed by a 5–3 majority of the City Council. With this authority, the mayor could delay the passage of an ordinance, require a revote and require a supermajority (defined as a 6–2 City Council vote) for adoption. Six years later, under 2004’s Measure P, the voters scaled back this authority, reducing the supermajority requirement to 5–3, essentially canceling out the mayor’s suspension power; if the mayor suspended an ordinance that had a 5–3 majority in the City Council, the same 5–3 vote would secure the passage of the measure in the revote, and the ordinance would be adopted.” Karlinsky, Sarah, Making Government Work, 2021 (pg. 12)

As one of only two two-term mayors in this millennium, I think Mayor Schaaf has an important perspective in this discussion. I will always be biased toward a strong mayor system because I worked for such an amazing mayor in Atlanta (Keisha Lance Bottoms). I would be curious and grateful to learn more about how a strong mayor system might have changed or impacted Mayor Schaaf’s two terms as mayor. From my experience, it was most helpful as a department head to know beyond any doubt that the boss was the mayor. I worked for an excellent administration and would be most happy to return to that type of professional environment.

Seneca, thank you for your comment. Former mayor Schaaf's commentary is focused on Oakland's form of governance-- an important and relevant current topic of debate. It sounds like you agree with her main point, which is that Oakland will function better with a strong-mayor form of government. With respect to ranked-choice voting, there is room in the charter reform conversation for other potential changes. It does not have to be limited to just one thing. Oakland Report is open to publishing other commentaries about charter reform, with ranked-choice voting being a particularly relevant aspect, and we invite you to submit your perspective on the topic. Thanks again.